Thoughts (blog space)

December 27nd, 2022

Ikigai 2.0—how to think about what to do

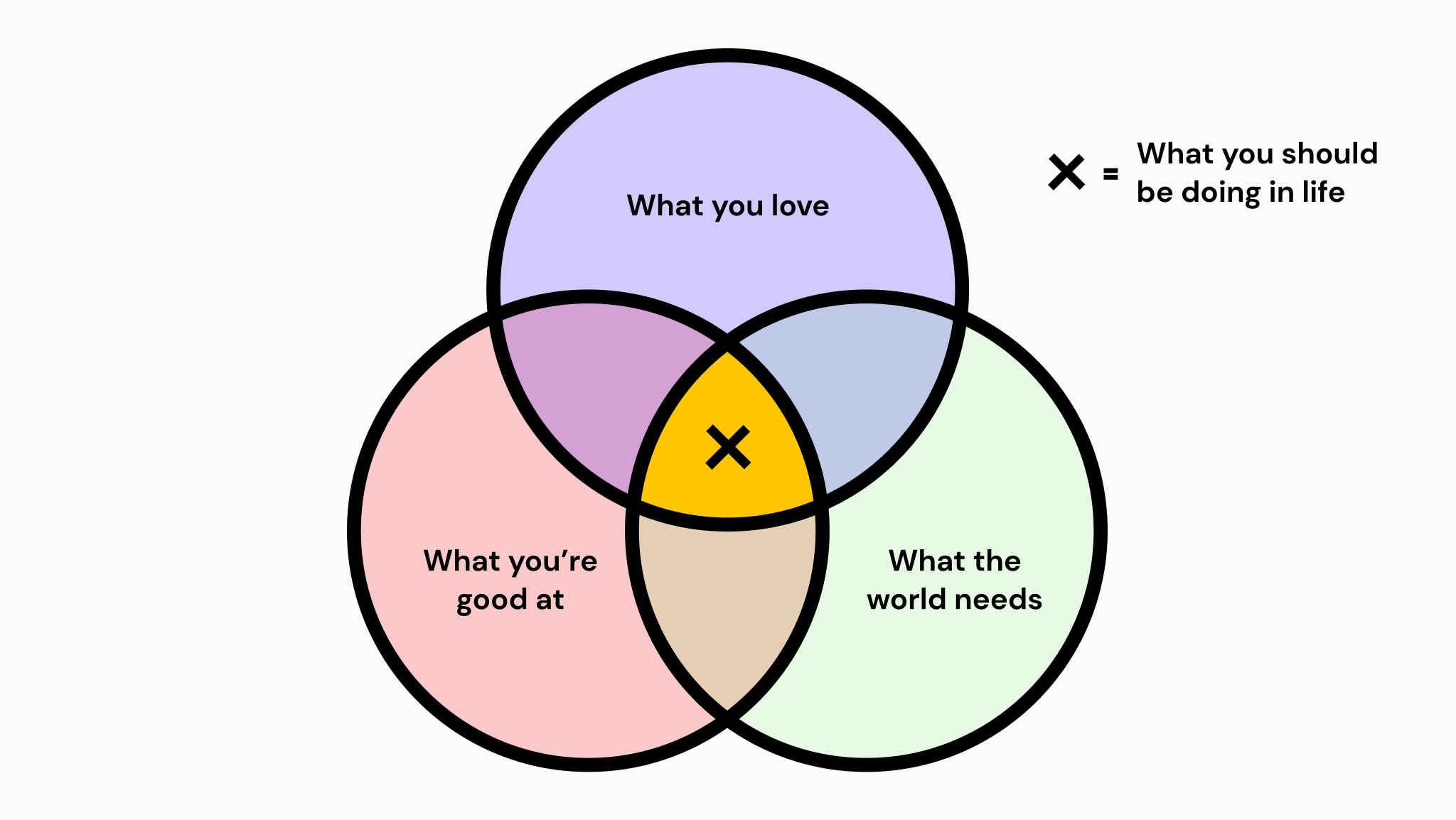

Ikigai is a Japanese concept that suggests your life pursuit (as it relates to your sense of purpose/meaning) should be the union set of 3 things:

- What you love to do

- What you are especially good at

- What the world needs

This is not the actual definition (it’s almost surely a Western bastardization of the concept) but it’s a convenient one whose purpose we can all appreciate.

There are probably several things that exist at this intersection for each person and it’s considered up to the individual to determine which of those to choose.

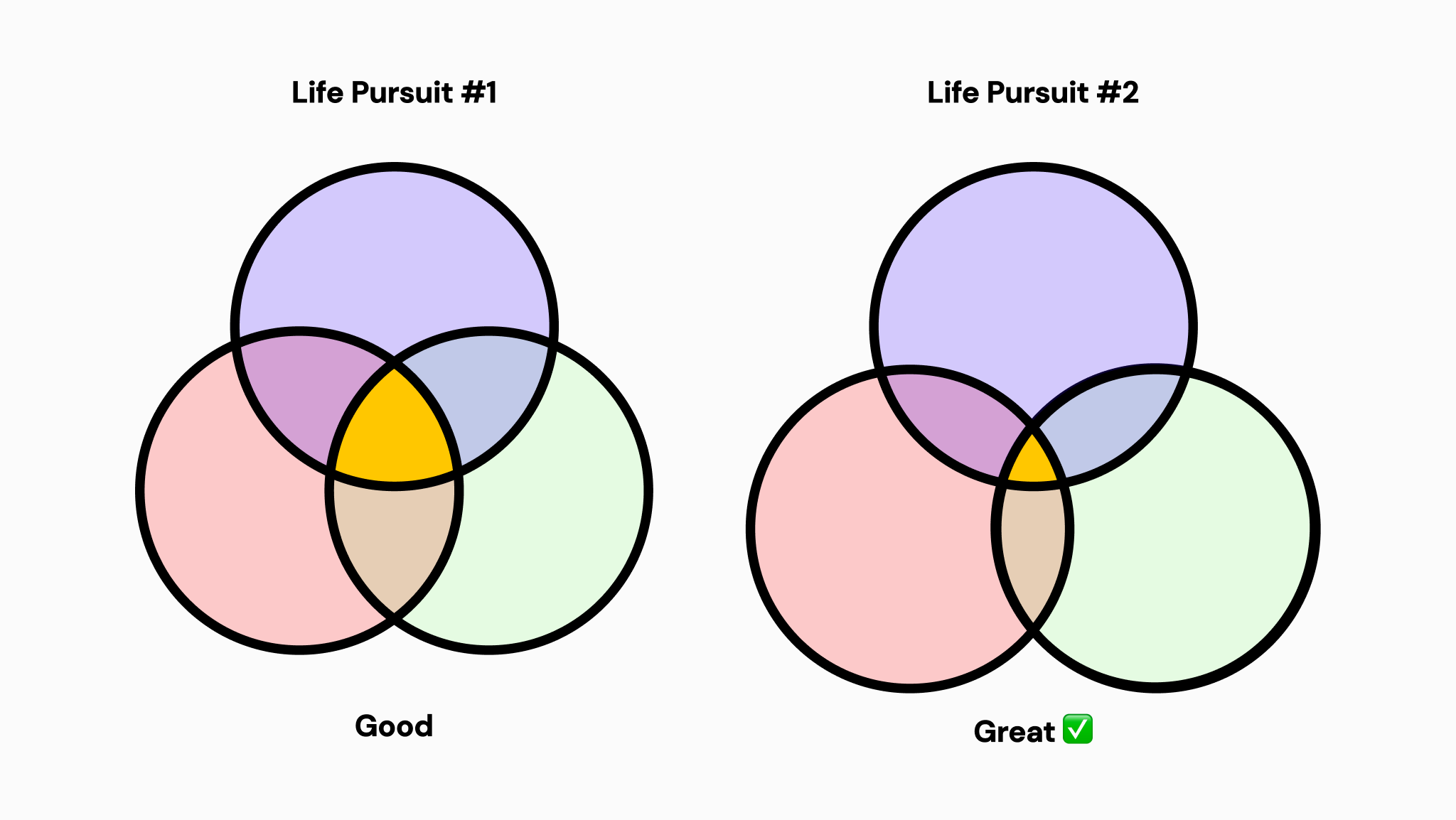

I would like to put forth an extension of ikigai which emphasizes pursuing the thing that has the least number of people who exist in that same intersection. That is to say, if the yellow area represents the union set of the three aforementioned sets, then one should find the element (or life pursuit) within that union set that is shared by the least number of people in the world.

For the visualization below, assume the size of the circles (fixed here for aesthetic purposes) represents the number of people in the world who share each quality (e.g. the number of people on Earth who also can do well what you’re good at). The area of the yellow space therefore represents Earth’s population size of people who exist at the intersection of those three sets.

The takeaway is that you should find something you are exceptionally good at, that you love to do, that the world needs, and that very few people can do. In fact, the fewest number of people possible. I believe contextualizing the number of people is a critical element of your calculation on the above that has not been captured by the conventional ikigai framework.

December 22nd, 2022

Do you optimize for information or ignorance?

Everyone should be an information optimizer. We all encounter difficult situations but how we engage with them varies. I think an important reframing of difficult situations is the following: where most people would see difficult situations as ones to avoid or delay, you, as a founder who cares about greatness, should be focused on minimizing ignorance and optimizing for information. A good way to optimize for information is to increase your surface area with difficult situations. This is beyond just “extracting lessons from difficult things”, a business/life platitude with which we are all familiar. Instead, this is about just having the most amount of information at your disposal to make the most informed decisions possible at all times.

For example, let’s say there is a possible rejection looming from a key investor, this should not be a process of procrastination and anxiety while waiting for the answer, this should be a process of running head-first into the situation such that you have the information you need quickly to queue up the downstream decisions. This framework is really a corollary of Ben Horowitz’s notion of running the right way (here). I think the reframing from an information perspective is key in that it emphasizes the constant game of information optimization.

This applies when it comes to interactions with colleagues, investors, friends, etc. I believe that radical transparency is about giving the other person the respect of full access to information that will help them make the right decision. More information means more degrees of freedom means larger potential solution space. Frontloading your access to those degrees of freedom quickly is important for obvious reasons.

That all said, there are downsides to this approach. Sometimes, optimizing purely for information can lead to optimization daemons that lead you down infinite rabbit holes without forcing a decision. One must be acutely aware at all times of what the right information threshold is to pull the trigger on a particular decision. I’ve fallen victim several times to information greed. Having an awareness of roughly where that correlation between data (input) and information (data relevant to decision) falls off is probably something that just takes time/experience. I’ve noticed my awareness of it get better with experience, at least.

So, in those moments where you feel a certain anxiety around the outcome of a particular situation, make sure to remember that you have the privilege of getting access to information that would otherwise be withheld from you and that your ability to make decisions will be augmented by the amount of relevant information you have available. If it’s an investor decision, for example, then either a rejection or confirmation will help you decide what the best action space is to pursue next. Be thankful for that opportunity.

December 6th, 2022

Don’t draw trendlines where they don’t belong

One of the great things about the human brain is its ability to accurately extrapolate out trendlines using very little data. While this ability proves largely valuable, we can become victim to it in ways that affect us negatively. In moments of emotional distress we default to extrapolating out the trendline prematurely and can often find ourselves feeling as though this distress represents some broader issue in our lives. My suspicion is we are great at identifying patterns but terrible at internalizing sample sizes. Sometimes data are not part of some broader trend and indeed just represent the current status of a particular situation. I try to be acutely aware of this tendency for either emotional valence. Be wary of extrapolating prematurely—with people, emotions, circumstance, or anything else.

March 29th, 2022

A way to think about thought

Preface

This is not a mathematical piece, this is just a piece that uses math to help us grok the concept of thought. It is pseudomathematical in both terminology and implementation—sometimes by design, other times by my ignorance. In either event, this is just the way I thought through everything and this piece is my attempt to bring you into that process.

Also, this essay ended up being more of a mind dump than a careful and calculated exposition about my framework. Please keep that in mind. Feel free to fork this and make whatever changes you think make sense—and, of course, to let me know when you do so. I hope you enjoy :)

Overview/Terminology

In trying to articulate something for another thought piece I was writing, I inadvertently devised a new framework I found even more exciting…

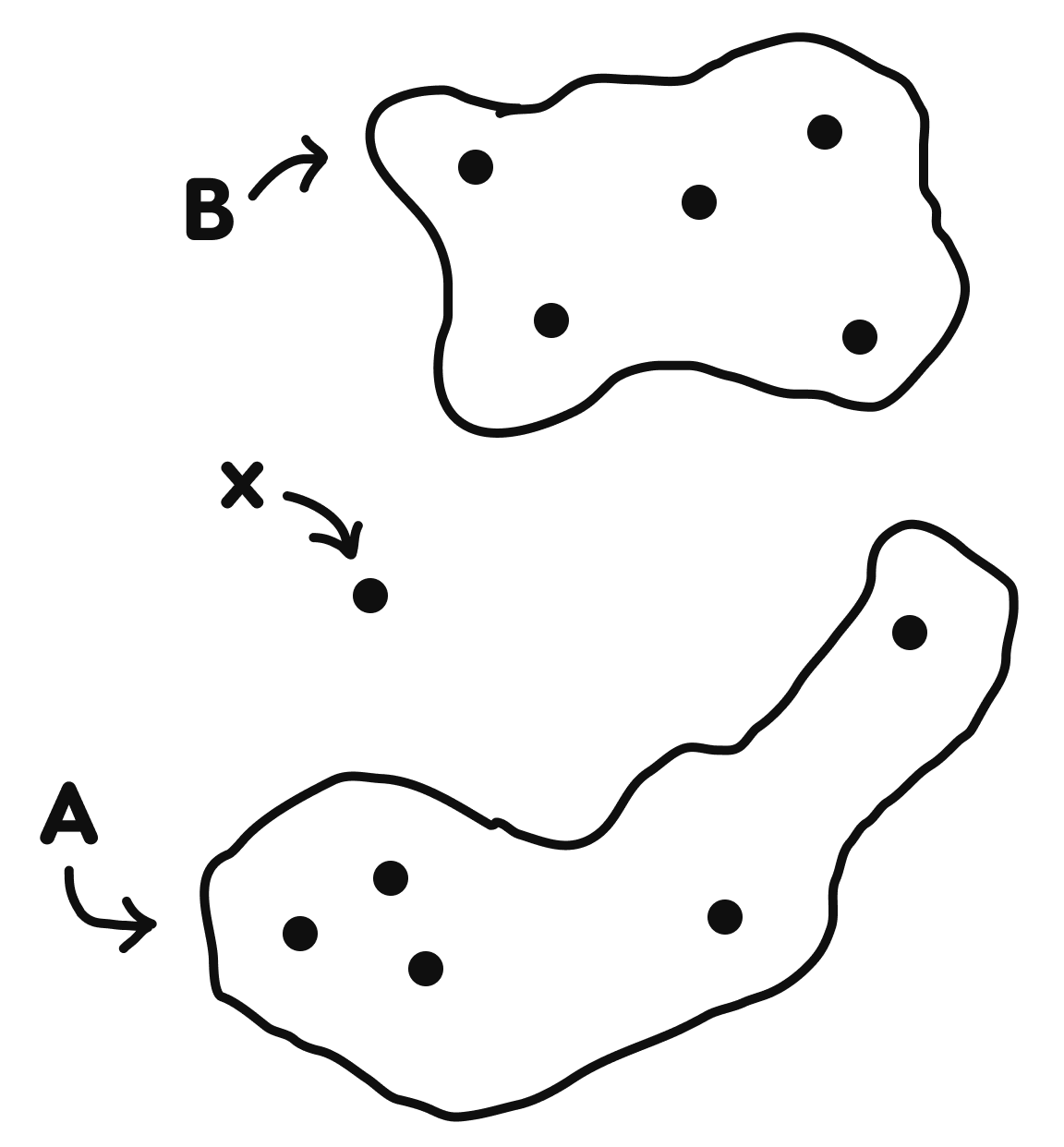

Consider two ideologies, A and B, projected into some n-dimensional idea or thought space. Each dot is an individual in that thought space, each with their own ideological composition that places them in a certain position in this thought space.

That weird shape “A” in my figure is an ideology, which I’ll call a “subspace”—that is, the minimum bounded thought space that encapsulates all individuals belonging to that ideology. People (again, those dots) with minor deviations from the accepted school of thought push the bounds of that ideology outward into new pockets of thought space. The morphology of the subspace is therefore determined by the ideologies of its constituent individuals.

“B” is an ideological antagonist to A. That is, there is no set of shared coordinates in thought space between A and B (i.e. A ⋂ B = Ø.) “x” is an individual whose current ideology is not readily defined (i.e. there is no publicly accepted label* for that individual’s ideas and therefore their position in thought space.)

*This is slightly misleading and so the nuance is captured below.

Expanded model

The proximity of x in thought space to a given subspace is an important component in determinining whether x will be subsumed by that subspace. One can think of it as the extent of ideological alignment—someone whose opinions may be aligned with Socialism but who has yet to classify themselves as such.

However, an important distinction is that it is not actual proximity in thought space to a given subspace but is instead the proximity to the nearest known subspace that is the relevant factor. If one is unaware of the existence of Buddhism but arrives at conclusions similar to Buddhist tenets, one will not become a Buddhist until it appears on their map of known thought space. They are only then even remotely likely to classify themselves as a Buddhist.

Now it only naturally follows that the likelihood of someone being sucked into that ideology, or subspace, is directly proportional to their proximity in thought space to that subspace. That is, the more aligned with a given ideology a person is, the more likely they are to convert. A corollary to this is that the likelihood of an individual not joining any defined ideology is directly proportional to the distance to their nearest ideology (again, not globally, but in known thought space.)

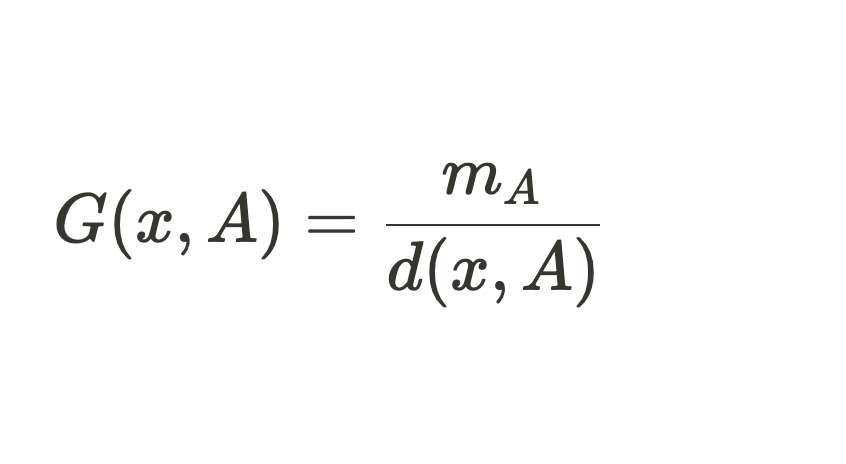

It might be conceptually convenient to think of each subspace in known thought space as having a certain graviational pull on all individuals. That gravitational pull seems most likely to be a function of its proximity to a given individual in thought space as well as its size (i.e. how many people are contained within the subspace, or ideology.)

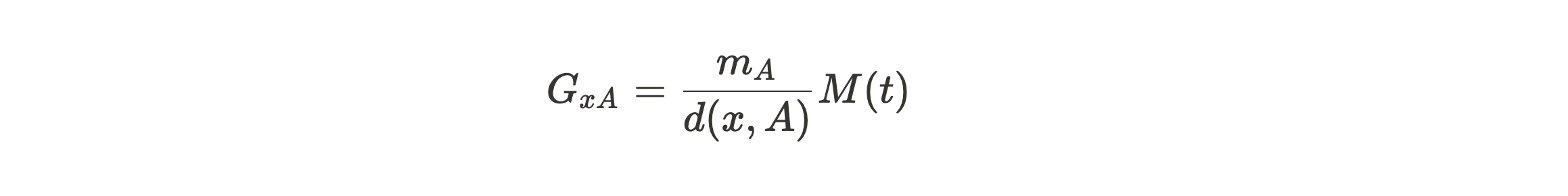

Where the numerator $m_{A}$ is the number of known individuals in subspace A and the denominator $d_{xA}$ is the Euclidean distance in thought space between person x and the centroid of subspace A.

It is important to underscore the fact that both variables are determined by the known thought space—that is, the ideologies, the number of individuals in each ideology, and the nuances of each ideology known to the individual. In instances where people’s average awareness of other ideologies is limited, a certain ideology can very readily claim dominance.

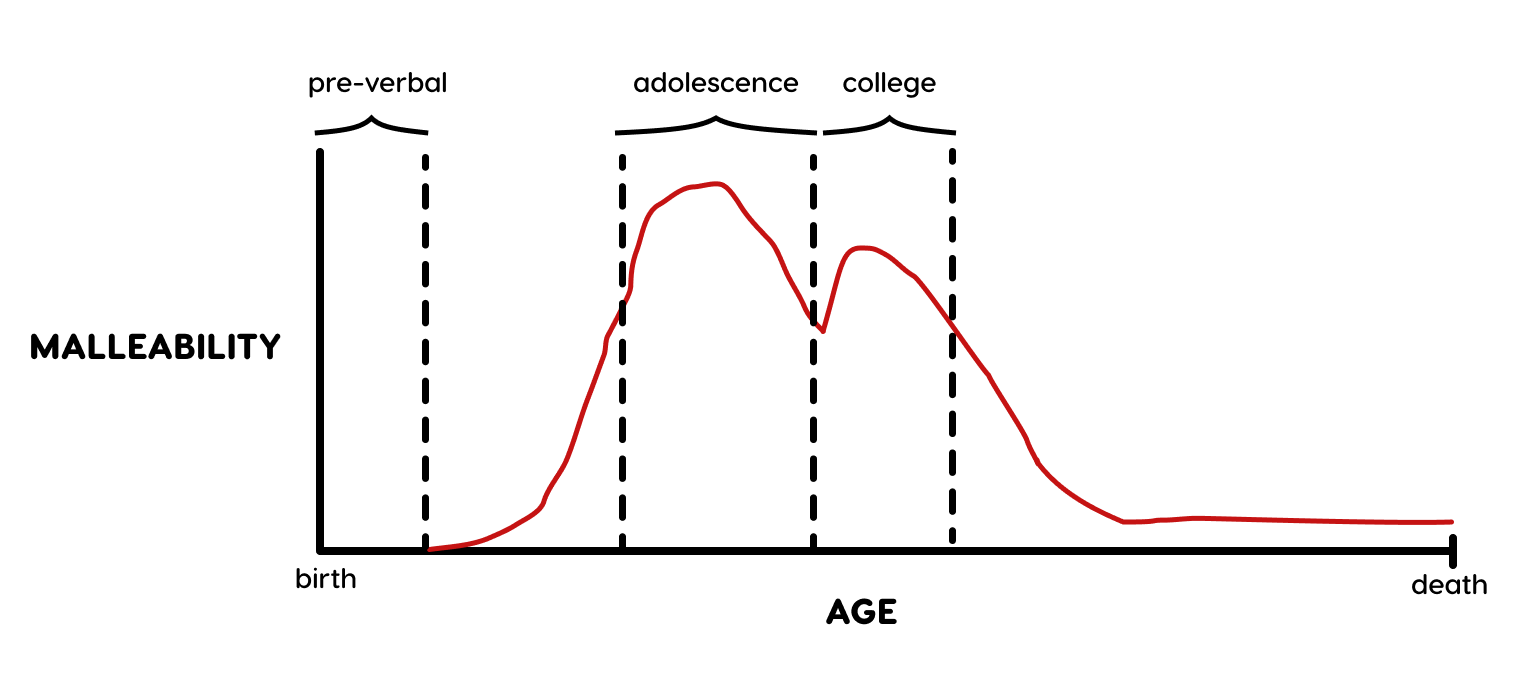

Another factor that feels important to capture in this model is the innate malleability of any individual, given their age. We can likely agree (I hope definitively) that one’s adolescent years are more formative than one’s late 60’s. This is not to say that ideological conversion is impossible at a later stage, it is just to acknowledge that there is an innate bias that predisposes people to being more receptive to ideologies at certain ages than at others.

You might argue with the shape of this curve (and we’d definitely both disagree about its relative proportions) but the important thing is that this malleability curve, let’s say M(t), is a nonlinear function normalized to the peak malleability of an individual throughout their lifetime. This serves as a weighting function for our “gravitational pull” equation. People are more malleable, or receptive, to the pull of ideologies at certain points in their life. We’re just looking for a way to express this “mathematically”.

So now to update the original equation…

With the only difference being that we are now also weighting the influence of an ideology by the malleability/receptiveness of that individual based on their age at the time of exposure.

Peak likelihood of indoctrination is likely during adolescence when the known thought space is minimal and the malleability is high. This basically affords an ideology unfettered influence over that individual, especially if the exposure to other ideologies is negligible.

Peak likelihood of conversion might come during college, where exposure to more ideologies is extreme (i.e. the known thought space broadens) and malleability is high.

Outliers

Given the information above, it follows that there must be some threshold of dissonance between the individual’s beliefs and the “mean ideology” (i.e. the centroid of the subspace to which that individual belongs) that causes a fracturing between the two (i.e. x no longer is part of A.) I see this as the point at which the individual would openly dissociate from the label of that subspace.

As nodes (individuals) start to cluster around a particular region, especially near the boundaries of a subspace, it makes sense that they might collectively split from the subspace with enough momentum (ideological meiosis?.)

Their likelihood of splitting is similar to the equation outlined above. The further on the periphery of an ideology they are and the more frequent and raw the exposure to each other’s deviations from that mean ideology, the more likely they are to split and form their own subspace. Think: denominations of Christianity that formed and continue to form.

Requisite for these types of subspaces to form is some medium through which these individuals/nodes can be made aware of one another. Prior to Gutenberg’s invention of the movable-type printing press, new subspaces were not able to form as easily given that the set of nodes whose position was known to other nodes was limited. That is, the known thought space for the average node was significantly more limited than it is today (duh.)

As communication technologies emerged they made more people more aware of other people and their respective ideologies. The average known thought space was broadened.

History has provided us with many such communication technologies (of all scales.) From books/literacy to cities to IRC to 4chan to Pioneer and more, substrates have and continue to emerge to facilitate quicker development of known thought space. As more nodes become more aware of global thought space more subspaces and conversions emerge.

As more nodes join each subspace, they strengthen its existence by broadening its boundaries (in both physical and thought spaces!.) This reflexively increases the likelihood of subsuming new nodes.

With increasing means of exposing individuals to global thought space, we can expect to see more ideologies/communities continue to emerge. This is already expected, of course, it is just pleasing to arrive to the same conclusion using this framework.

Nascent subspaces and their formation

Martin Luther would not have been able to spark the Reformation without making people aware that other people were aware of his nascent ideology (early use of network effects.) Communication tools serve as a substrate through which the average known thought space of its participants broadens.

Real-world implications

I believe there are some real-world implications for this framework. Consider for instance the targeting of youth for ideologies of various kinds (e.g. Christian Camp, Hitler Youth, Boy Scouts, etc.) Indoctrination 101… This framework potentially offers a crude way of modeling the various factors that drive the adoption of those ideologies—that is:

- the innate malleability or plasticity of people of a certain age

- the number of people they are exposed to who believe that ideology

- the extent of their awareness of other ideologies

- the extent of ideological alignment with other ideologies of which the individual is aware

This also provides a convenient way to think about how limited exposure to other ideologies breeds blind dogma—think: the feedback loop of social media echo chambers, people in remote regions who have limited exposure to people of the “opposite” political persuasion, etc. Conversely, we can also see how exposure breeds intellectual diversity—in this framework, new subspaces (or ideologies) invariably emerge from exposure (i.e. expanding known thought space.) People who live in big cities likely have broader known thought spaces than those who live in rural regions. For politically inclined adults who move to big cities but still are blinded by dogma, this is also explained: their M(t) (malleability) is so low that the gravitational pull of another ideology that would otherwise exist is significantly reduced. This is not at all to say that it is impossible to have conviction in a big city—it is just to say that the constant exposure will on average erode that hypothetical max degree of conviction.

Final thoughts

This framework is incomplete (and possibly incoherent..?) I will plan to expand on it as both time and my headspace allows. For now, I’m posting prematurely to feel the pressure of random eyeballs as well as to get feedback in the process. Thanks for reading!

February 18th, 2022

My secret side project

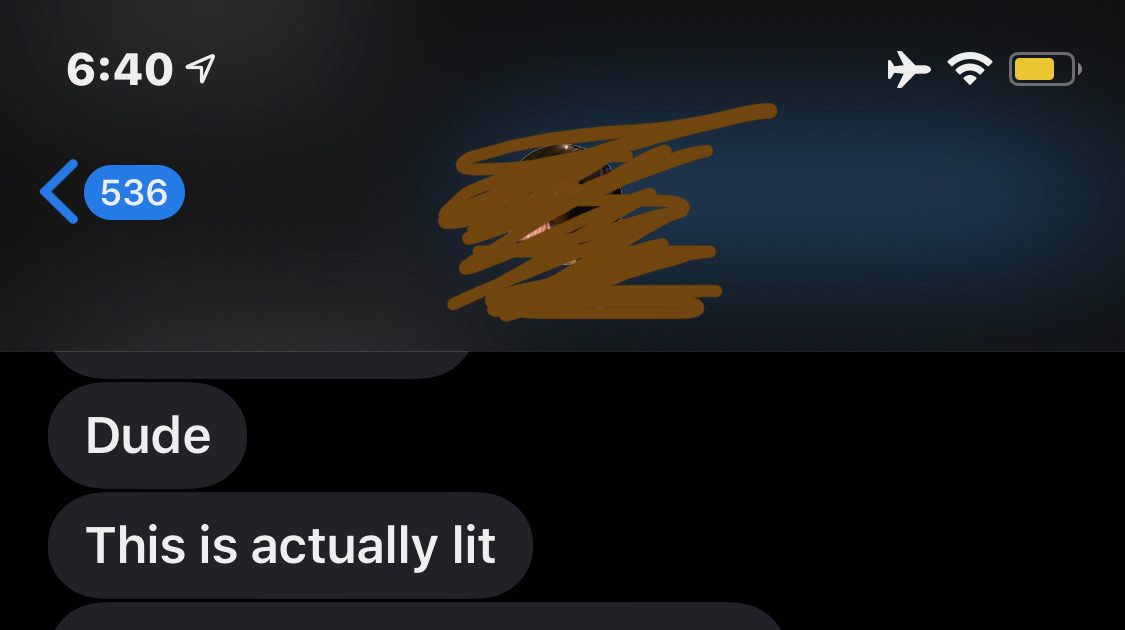

On a gorgeous Hawaiian day in late December I whipped together a little script. For various reasons, I am keeping the purposes of this script secret. What you need to know is that this little script was birthed from the confluence of my boredom and my randomly reading API docs of a popular mobile app. I thought of a cool feature one could build using the API and built out a pretty basic service in a few hours. I sent my MVP to a close friend in consumer social. 10sec later he texts back…

He gives me the idea for an improved derivative of this product and suggests we productize and ship that new product in the next 2 weeks. We partner up with one of his colleagues to build out a website and productionize my little MVP.

I whip together a sufficiently scalable backend and clean up my script. My friend designs a simple website which his colleague builds with a basic API layer to interface with our db. We reach out to some TikTokers to post and within a day we’ve locked in the campaign.

After some basic stress tests, we feel we are ready and the first TikTok post goes out on Jan. 16th. Within the first 22 days we get the following data:

TL;DR this project is still in its infancy and we initially got obliterated by the demand (crashing servers, blocking/delaying services, etc..) We have a lot of conviction in the project and are going to start properly ramping up the growth. This was all just a very prelimenary test-run.

I’ve realized in pursuing this side project the power of rapid exploration. This flies in the face of what most founders are taught to believe. People in tech overindex on the merits of shipping products the conventional way (i.e. come up with an idea, make a pitch deck, reach out to investors, build out an MVP after hiring the 10x engineers you convinced to join, tell everyone on LinkedIn you’re the CEO of a future unicorn despite the fact that all you’ve done thus far is incorporate with Stripe Atlas, etc..) Even as kids we are trained to think so definitively about things—”I will be an X one day”. Why not just give it a shot and reassess in a couple of weeks?

This approach is not per se a prescription for anyone considering pursuing a startup but moreso a recommendation to those who are capable enough to build products and curious enough to indulge that capability. Just build something casually for 2 weeks and make sure to get it to market fast enough to determine whether it’s worth pursuing further.

If you are toying with an idea, I suggest you:

- Quickly (1 week MAX) build an MVP (if you are technical—if not, then make a Figma protoype)

- Text the absolute minimum number of people you need to see this project through to completion to collaborate with you (2 other people MAX, in my opinion)

- Make a compelling landing page with at least a sign up field

- Launch using TikTok and make an assessment in 2 weeks as to whether the product is worth pursuing further (spend no more than $2,000)

The opportunity cost is completely overshadowed by the potential upside for these side projects. I want to advocate heavily for lowering the mental friction of starting a project. Start putting together something cool tomorrow and let me know how it goes (DM’s open on Twitter!)

March 23rd, 2021

Change vs. Progress

It is incredibly important not to conflate change with progress.

Progress exists at the intersection between change (state B ≠ state A) and growth (some optimization towards the objective). Change can exist without growth (e.g. a new presidency, binary fission of a bacterium, etc.), but growth cannot exist without change (some sense of modification is requisite for optimization).

Without a driving force towards growth, the action or change will be what we can call “yieldless”. For example, if I choose to go running, the act of running itself may in fact be the objective, and that will hold under any context in which I am running. However, if my goal has shifted to using running as a means of achieving something else (like moving from point A to point B), then the actions that progress me towards that goal become contextual—running on a treadmill achieves the same action without any progress (as defined by the context). By the same token, science has the bad habit of feigning progress where, in most instances, we are simply just running in place.1

It is very easy to see changes within science and be excited by the carrot of progress, but how have those changes progressed us towards the initial objective? In medicine, as an admitted generalization, the objective function is easily defined: are we closer to curing the disease in question? Without proper heuristics for determining this, yiedless changes can safely hide under the veil of progress.2

I suspect that we would benefit greatly from inoculating ourselves to the allure of change and no longer misconstruing it as progress. Who would have thought that using the ultimate goal to guide the action could be so hard??

1The iPhone, as another example, has arguably undergone many yieldless changes over the years (compare the growth rate of the product quality in the early years of the iPhone to now), yet the illusion of continued progress has been upheld by the consistency of these iterations.

2Collison and Cowen’s 2019 piece on this (here) outlines the urgency of establishing these heurestics across industries. It’s a great read.

Novemeber 3rd, 2020

Reflexivity in politics

Distributing poll results to a population before an election degrades the predictiveness of that population by a significant margin. Is there a psephological law for this? I’m not sure, but there should be…

In 2016, I warned my family and friends that distributing polls that predict a landslide in Clinton’s favor would result in mass complacency, and that this complacency would manifest as poor Democractic turnout. If my community of friends is at all a microcosm to the younger population in the United States, in 2016, ~10 of them (likely more—I only asked a small handful) did not vote because “Hilary [was] going to win in a landslide… No need to go through the pain of voting”. 3 of those 10 friends were from Florida, a crucial swing state in that election. I fear that the same thing may happen with this election today.

While I am not confident in the final outcome of this election, I do feel comfortable positing that the final result will be much closer than predicted by any leading pollsters.

The point here is that I think that there is a lot about reflexivity that remains unexplored and believe that finding elegant ways to mathematically model reflexivity in different systems would be of immeasurable benefit to statistics, economics, neuroscience, and beyond.

Shockingly, the “error” of the pollsters’ predictions in 2016 was actually pretty much at the mean combined error for past elections (only 4% higher than the average). It should be noted that these data are weighted by the number of polls put out by each institution and so the most active pollsters are weighted the highest. The interesting insight here would be to see whether there is a correlation between this weight and the error itself, since the most popular pollsters can be expected to be covered by big media outlets more than their counterparts. The more media coverage a poll receives, the less likely it is to be correct.

June 1st, 2020

Some questions…

A few random things that I’ve been thinking about quite a bit. Some date back years, others in the past few hours

Why does it feel like Hungary disproportionately produced some of the brightest and most prolific minds of the 20th century?

- Erdos, von Neumann, Gabor, Wigner, Elo, and many, many more

How can we quantify the changes to a predicted outcome after that prediction is disseminated to the population whose behavior is being predicted?

- Think: election polls, distributions of wait times, etc. Is this sufficient to describe the glaring errors of all the 2016 US Presidential polls?

What city in a Third World country will bear the greatest intellectual fruits in the next 25 years?

- Lagos? CDMX?

Why has the wash time of restaurant-grade dishwashers (~1min) been so disparate from its domestic counterpart for so long?

- I’m not convinced that this “industry-domestic discrepancy” exists to the same extent for other applicable technologies, especially not for so long (the processor in your iPhone is 5 orders of magnitude more powerful than that of Apollo 11)

Is globalization always a good thing? And to what extent does the globalization of technology align with (and also engender) cultural globalization?

- China has reaped the rewards of Western innovation without the “burden” of democracy (great convo on this here), yet it does not feel that this adoption has been at the cost of any cultural identity. On the other hand, the physical presence of Turks in Germany has had profound influence on the culture (and cuisine) of the latter, though their relationship dates back to at least WWI (before US-China relations) so maybe the comparison isn’t fair.

May 9th, 2020

My take on the COVID-19 market

Disclaimer: I am not recommending any specific stock purchases here, nor am I licensed to do so. I merely want to share the thought processes that helped me profit during the volatility effectuated by COVID-19

People have been scared.

It makes sense, how could you not be when there exists the incessant echo chamber that is contemporary media? Call it ignorance, but I usually never listen to stock recommendations or follow markets through any particular media outlet. My investment approach could not be simpler: I think about the market, I substantiate or uproot my hypothesis with market data, and update my internal model of that market using these data.

A reasonable response would be to laugh. What the hell do you know, punk? Well, not much, but enough to consistently beat out some of the weirdest markets in the past 3 years and hold a constant >30% returns for that time. I have helped my family, other families, and my friends invest in the market, because at its best, it’s a lot of fun.

I’m no guru, I just love contrarian thinking. Thankfully, this translates well in investing: flying in the face of conventional wisdom, in late 2018, I shorted FB and AAPL based on a theory I had about their self-imposed pigeon holing. If this sound stupid, I encourage you to check out their stock prices for that year (P.S. I made >350% returns from those puts). Big money is made when you are right and the majority is wrong (see Burry, Dalio, or Soros). If everyone says I am wrong about a prediction, it’s often an incentive to chase the idea further.

Back to 2020… COVID-19 has taken a huge chunk out of the economy, a chunk which is almost perfectly distributed across each industry. On March 10th, I was debating with my mom about this investment climate, as she was consumed by anxiety about the stock market and how the experts were saying it would be a recession (I remain pretty convinced that an imminent threat of such magnitude to the economy that’s universally accepted as likely will in fact beget solutions that prevent it from actually materializing. These things really are reflexive in that way and every major economic recession has blindsided the majority, that’s why they happen! That’s probably for another blog post, though).

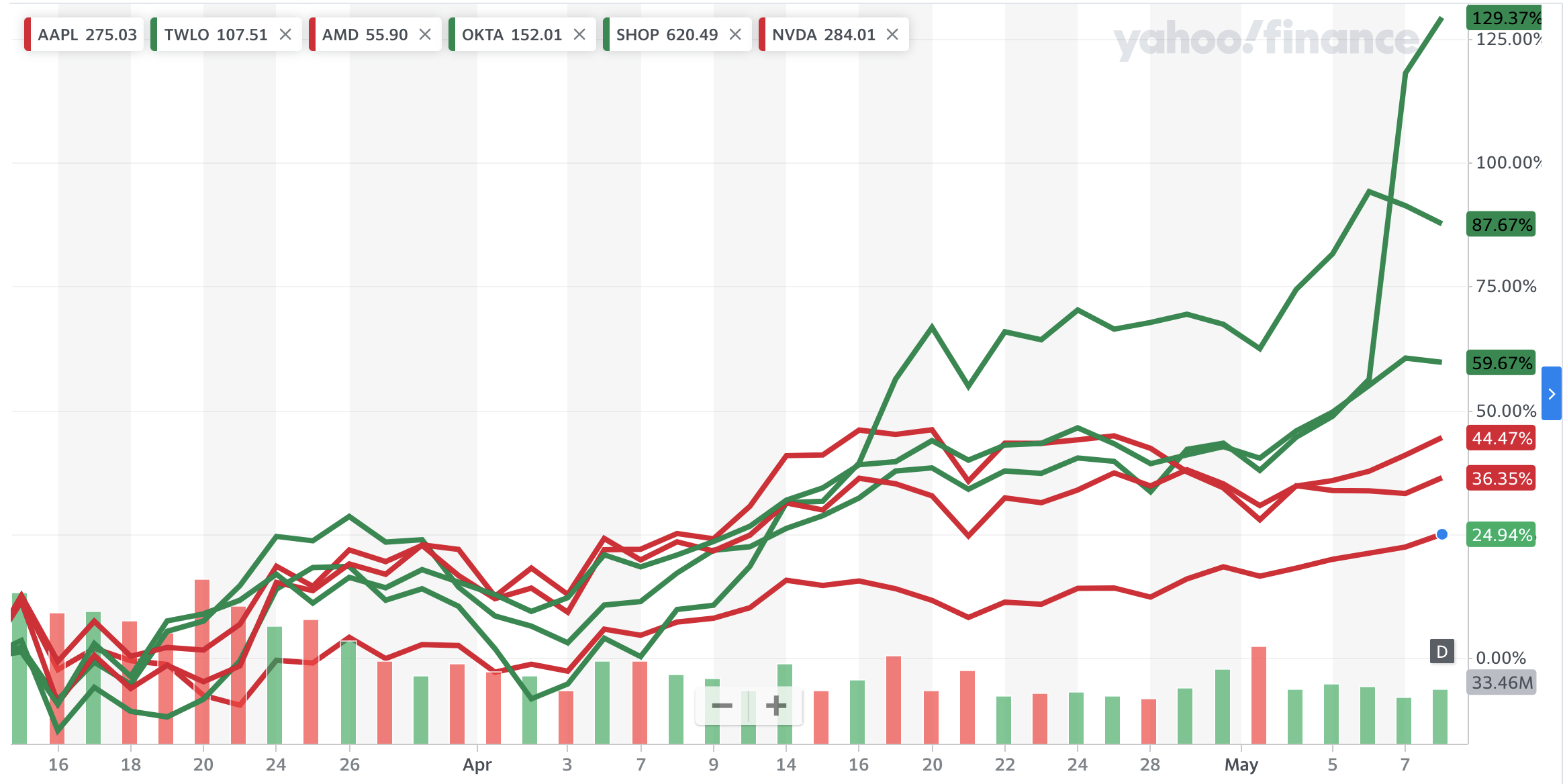

My mom, in line with the rest of America, was convinced that everything would plummet and that it would be a year for any of these stocks to rebound. I thought this all over… Just looking at the tech industry, it would make sense that hardware companies would be severely impacted—a lot of these tech behemoths got a cold splash of water exposing their overdependence on China (as if the ongoing trade wars weren’t enough). These hardware companies (e.g. AAPL, NVDA, AMD) now have to rethink their entire supply chain. The software companies (e.g. TWLO, OKTA, SHOP), however, should be much more nimble and unaffected by the downturn, right? Teams of programmers should still be able to deploy code from their bedrooms and people should still consume their products remotely.

As it turned out, the aforementioned industries (and individual stocks) were affected equally, and I just knew that the software stocks would rebound earlier. I’ll let the data speak for themselves:

Stock returns from 3/10/20 - 5/9/20 (green = software, red = hardware)

Now before you think that I retroactively changed my selection of stocks to sound smart in a blog post, these were the actual 3 that I recommended. I should probably say that I’m still invested in TWLO, and have been for years (first bought at $76/share), but I sold off all my other stocks about 5 months ago when it became too time consuming.

These differences may seem slight, but the worst performing of my recommendations is 134% of the biggest return for the aforementioned hardware companies (and TWLO returns are 519% of AAPL returns for this period!).

The point here is that intuition and calculated thought can be an important factor in distinguishing you in investment. Don’t believe me? Billionaire George Soros literally moves millions of dollars based on pain in different parts of his body. Everyone else uses financials and the same old indicators—be different.

April 19th, 2020

The crucial missing link for Artificial Neural Networks

I’m going to jump right into this one, so apologies if it lacks the technical introduction such a post might demand

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), as the name might suggest, were built with the brain as a primary influence—artificial neurons connect to each other, each conferring signals to others and each with connections that vary mostly in accordance with the alignment between the neuron’s activity and the ultimate achievement of the system’s goal (see objective functions). This was a breakthrough in the field of computer science as it completely transformed the capabilities of computers to achieve complex tasks. Computers were no longer just efficient computing devices that did simple tasks quickly and consistently—they now could improve iteratively (see Perceptron and the lesser appreciated MENACE).

Things have improved a lot with regards to computing power since those early days, but the reality is that the fundamentals of ANNs simply haven’t witnessed the same growth.

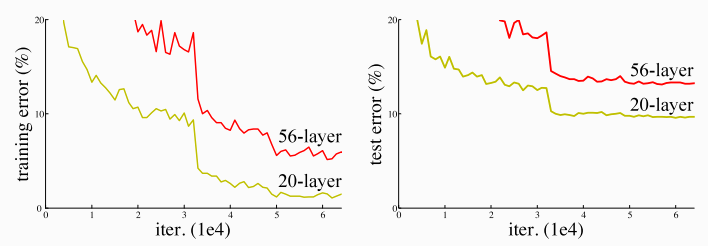

What we see is that, despite the fact that we can reach unprecedented network depth, performance just doesn’t scale. Part of this is due to what is dubbed the vanishing gradient problem, in which the changes made to the connections of neurons deep into the network are negligible and therefore less likely to contribute to the final network output. This problem was significantly alleviated by the development of ResNets, the original version of which broke numerous world records for image classification and other tasks. However, increasing the depth of this network still results in a performance plateau at a certain depth (the error difference between 50 and 100 layer ResNets, for the tasks I’ve used them for, is negligible). How has increasing the number of neurons, connections, and layers to unprecedented heights in our ANNs not brought us within reasonable proximity to the cognitive powers of the brain?

Take a look at how performance of a basic network can actually get worse by adding layers (image classification network on CIFAR-10 dataset):

Deeper version of network does worse at image classification

It’s clear that a network with connectivity as its only parameter is insufficient to generate the flexibility of the brain.

I believe that the most significant factor missing from the way we build ANNs that is present in the brain is electric fields. While artifical neurons in ANNs are mathematical representations, biological neurons (just “neurons”, from now on) occupy physical space, and thus their interactions are influenced along a spatial dimension (Note: I definitely do not consider layers of an ANNs as spatial). I also believe that the importance of the electric fields emitted by neurons is severely underappreciated in the field of neuroscience, despite the vast evidence for their significance in the biophysics of the brain as well as cognition (here and here, and I’m comfortable arguing that the breakthrough of LFPs is because they register both action potentials and the resulting electric fields).

The electric fields emitted by active neurons contribute to the complexity of the entire system by being reflexive—an active neuron emits a field which in turn influences the firing dynamics of that neuron and the surrounding neurons, which influence downstream neurons which in turn emit electric fields which in turn… you see where this going. The result is that groups of neurons in the same vicinity will collectively generate large electric fields that will modify their biophysical signature and possibly enable computations that are otherwise unachievable in a state of individual isolation. The fact that neurons are exist in the world of biology has been seen as a hindrance to their computational abilities (slow time constants, high noise, energetically expensive, etc.), but the reality is that such complexity simply could not exist on a processor and instead only in a biological system, or one that merges the two.

Anyway, the point here is that for ANNs to approximate or surpass the complexity and cognitive flexibility of the brain, they must first address this issue. I think embedding actual neural tissue in circuitry (“wetware”) is a really smart way of tackling this, and I’ll be keeping my eye on Cortical Labs, Koniku, and maybe even this nutjob (who did the inverse).

April 10th, 2020

Humanity has already found the neural seat of consciousness, science has just overlooked it

If someone put a gun to my head and made me blurt out the part of the brain that houses consciousness†, I’d say “thalamus” without breaking a sweat.

The thalamus is a chunk of gray matter found in the forebrain. This is the Grand Central of the brain—it receives input from a vast number of areas and its projections innervate almost all sections of the cerebral cortex. The result: the thalamus both integrates and distributes information from countless areas. For instance, if sensory input comes in, the thalamus works its magic (transforms that sensory information along some dimension), and then spits it back into the sensory area from whence it came.

I believe quite strongly that anticipation is an evolutionary prerequisite for consciousness and that it demands the coordinated integration of the senses. Why does anticipation require the integration of the senses? Just think about it: let’s say a person is swinging a punch at you. Well, first of all, you would need to calculate the trajectory of their swing (motor cortex) which would require that you visualize their fist reaching your face (visual cortex). Significance is assigned to avoiding their fist reaching your face because you know that it will hurt (nociceptors). All of this activity coming from disparate regions of your brain before the fist has even come near your face. Without the tight and timely integration of all the information, you can bet your ass that tomorrow you’d wake up with a black eye…

Why is anticipation a requisite for consciousness? Because anticipation itself requires:

- An internal, updatable model of the world (think: Bellman Equation)

- A sense of futurity (not just living in the now, but in the next)

- Pattern identification (I would feel pretty comfortable positing that this is the product of the other two)

I am putting forward that these 3 pillars are the building blocks on which consciousness is built. If we could find regions in the brain that encode or enable these, then I’d say we are well on our way to uncovering the secrets of consciousness.

Back to the thalamus… Just based on sheer connectivity, it seems like the thalamus has always been a prime candidate for understanding neural processes on a fundamental level. Why has it taken so long for focus to shift to the thalamus? The thalamus has historically been viewed as a “low-level” (yuck!) center (yuck yuck!!), as part of a contrived framework of anatomical hierarchy in the brain. Everyone learns in their 101 courses that “the midbrain is the lower brain… and the thalamus and associated areas are part of the limbic system” (here, here, here, and here). The fact that they peddle this crap to unwitting freshmen is infuriating! “Experts” loooove to talk about the limbic system, also called your “Lizard Brain” (yes, experts literally call it that). These experts have grouped the thalamus in this category based on the antiquated idea that neural anatomy recapitulates the evolutionary development of the brain. In plain English: the deepest parts of the brain are the ones most like our evolutionary ancestors. As an unfortunate consequence of this antiquated school of thought, the thalamus has unfairly been identified as a primitive area, with little historical investigation into its role in cognition! Individuals and scientific communities are influenced deeply by egos and the perception of fundamental truths—scientists are unwilling to accept novel discoveries if they fly in the face of what the scientists fundamentally believe to be true (or if they spent most of their life committed to that which is being overturned). This has largely stifled investigation into the thalamus and acceptance of the promising results that come out of it.

Mike Halassa at MIT is one of the few scientists who gets it. He’s still relatively early in his career but I am willing to predict that he will be one of the pioneers of his generation that will unhinge our current understanding of the brain (see also Doris Tsao and more recently, Steve Ramirez). If you’re looking for a good read on the thalamus and cognition, Halassa’s paper Schmidtt et al. 2017 is seminal. In brief, the paper demonstrates that thalamic neurons engage in task-relevant computations that freely transition from object-based to task-based. This means that the thalamic neurons can encode the identity of specific stimuli as well as their significance. Importantly, these thalamic neurons were found to regulate activity in the pre-frontal cortex (PFC), which is largerly seen as the most significant center in cognition. This means that the “low-level” area was not merely relaying basic sensory information from the PFC, but in fact was responsible for conferring its cognitive flexibility!

Mike and I had a great discussion last November about this fundamental oversight in the field and how overwhelming the evidence is for the thalamus’ role in cognition. The ingredients for the thalamus coming out as the neural seat of consciousness are all there—it integrates and distributes information from the broadest reaches of the brain, it confers the “high-level brain” the ability to transition between definitions of identity (object –> significance), and has been overlooked in the field for reasons unrelated to its significance in the brain (no one has gotten far trying to find consciousness in the brain, so maybe they should start looking under their noses!). I am super excited to know that this fundamental transition in the field of neuroscience is imminent and will be keeping a close eye on it all from afar.

†Defining consciousness is not something I will dive into here, despite some implicit definitions. That’s an unproductive rabbit hole to be avoided when trying to identify candidate neural substrates for consciousness

Bonus: Google Trends for “thalamus” (I promise this won’t be my only data source) shows an incredible periodicity with annual maxima every October going back to 2007. Can you guess why? :)

April 8th, 2020

Brown Gold: How our poop is the most untapped gold mine of the 21st Century

Poop, and by extension, wastewater, is a data source that will be replenished each minute of every hour of every day until the end of civilization. The microbiome is severely underappreciated in medicine and health†. I’ve always been puzzled by this… The evidence supporting the significance of the microbiome is almost insurmountable (Alzheimer’s, longevity, obesity, autism. The list goes on…), so how the hell could this be almost universally overlooked?

Most recently, researchers discovered that sewage water serves as a useful proxy for the extent of COVID-19 infections in the community. This made me wonder: why haven’t we done this before?

What we have is a fundamental misalignment in the current and actual values of this asset (poop). Call it arbitrage or just plain old opportunity—the reality is clear. Wastewater is (literally) the shit that no one wants (well, a few people), and so starting to collect mass samples of wastewater wouldn’t really perturb the existing system too much.

Despite all this, public interest in the microbiome seems to be stagnant:

Okay, these might not be the most convincing data, but it’s a start… Clearly the public appreciates the importance of health and bacterial diversity, but why don’t people attend to the microbiome as an extension of that?

This space is going to make a select few a lot of money. The factors for success are all there: a paucity of competition, an almost infinite abundance of data, simple means of data collection, and a demonstrated role in domains relevant to health and disease… These are fertile grounds for discovery and the intrepid pioneers that get in early will no doubt be rewarded.

Let not thy wastewater be wasted… You heard it here first.

†I can name a couple good companies that recognize this systemic short-sightedness: Pendulum Therapeutics and Gingko Bioworks. For the interested reader, I also recommend looking into Richard Sprague, who has a pretty extensive passion project on his own microbiome

Thoughts on any of these articles (whether agreeable or otherwise)? Shoot me an email